This year has already been a big year for space exploration. The New Horizons probe has just sent back the first pictures of the pink snowman – otherwise known technically as (486958) 2014 MU₆₉ – in the Kuiper belt. We also know it as ‘Ultima Thule’. Ultima Thule is the nickname given the little contact binary by NASA. But it is also a traditional term for worlds far beyond our own. The first pictures came through on Jan 2nd, but the closest flyby (chart) took place on New Year’s Day at 12:33 EST. It was discovered on 26 Jun 2014 at 08:52 UT (chart) in the constellation of Sagittarius in its retrograde phase. Its current astrological position is at about the halfway point of Capricorn. I haven’t bothered to calculate the exact degree, but it is a little past 19 hrs. RA. There is no online ephemeris that has this one in its database that I know of. But that is not our biggest story, although it is grand enough.

Horizons probe has just sent back the first pictures of the pink snowman – otherwise known technically as (486958) 2014 MU₆₉ – in the Kuiper belt. We also know it as ‘Ultima Thule’. Ultima Thule is the nickname given the little contact binary by NASA. But it is also a traditional term for worlds far beyond our own. The first pictures came through on Jan 2nd, but the closest flyby (chart) took place on New Year’s Day at 12:33 EST. It was discovered on 26 Jun 2014 at 08:52 UT (chart) in the constellation of Sagittarius in its retrograde phase. Its current astrological position is at about the halfway point of Capricorn. I haven’t bothered to calculate the exact degree, but it is a little past 19 hrs. RA. There is no online ephemeris that has this one in its database that I know of. But that is not our biggest story, although it is grand enough.

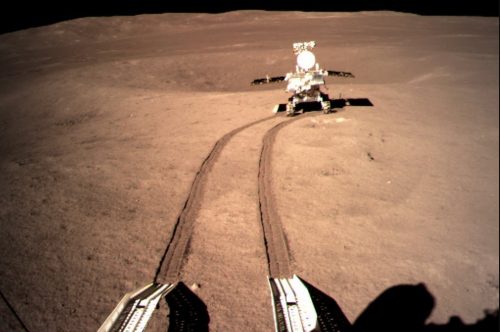

The bigger news is the landing of the lunar module Cháng’é 4 by the Chinese on the dark side of the moon, the first of its kind. Why it is more important than the New Horizons flyby will become clearer as we go along. This is the 4th moon mission by the Chinese and the 2nd that involved a landing. The Cháng’é-3 also landed, but on the near side. So, this will be an article in two parts, the first dealing with background on the mission and its implications for geopolitics and the second part with the more esoteric and philosophical side. But before we get into the mission specifics, there are a few points to be made about the so-called ‘dark side’ of the moon.

First of all, we are not talking about an album by Pink Floyd of the same title. That aside, the moon is tidally locked with the Earth, meaning the same face of the moon faces the Earth at all times. This means that we have never seen the other side of the moon until the last few decades, when spacecraft were able to give us the vista. It was an unknown quantity, hence we called it the ‘dark side’. It has been occulted to us due to the tidal locking. So, there is another thing we can set aside: the far side of the moon is neither mysterious any longer, nor is it occulted any longer. There is nothing sinister about the far side of the moon – the latter being a better appellation for that lunar hemisphere than ‘dark’.

Further, the far side of the moon receives roughly the same amount of light as the near side. When the moon is between the Earth and the sun the far side is fully lit, being fully exposed to the sun, and vice-versa when the moon is farthest away from the sun. Thus, at the new moon the far side of the moon is fully lit, while the near side is in darkness, and vice-versa for the full moon. So, here are the big questions, aside from our curiosity about what is on that side of the moon: Why do we want to land and explore there, and why have we not done it before?

In answer to the first question, it turns out that scientists have suggested (I don’t have more names for these people, sorry) placing a radio telescope on the far side of the moon. Why? Because there would be far less radio interference from the Earth and the signals from ‘out there’ in space would be far clearer than they would on Earth. The Earth is now awash in radio signals, especially at the frequencies involved in radio telescopy. And satellites are a potent source of this radio noise. A second, more nefarious reason for setting up house there is because no one can see what you are doing there from the Earth. That is quite convenient, if you are into that sort of activity. The only problem is that such activities cost a lot of money, funds better spent here on mother terra. Another reason we would want to explore the far side (no reference to Gary Larson) is because it is believed to have higher concentrations of Helium3, an isotope of helium that shows promise in future fusion reactors. It is said that there is enough of the stuff there to power the earth for 10,000 years. And then there is thought to be an abundance of resources there, especially rare earth elements. But most of these ideas lie further into the future, like decades away. However, first we have to know what is there, which brings us to the mission.

The Chinese mission is actually in three parts. First, in order to beam radio signals back from the far side, one has to have a satellite in stable orbit at the lunar Lagrange-2 point, which gives the satellite a stable halo orbit around the moon with a full view of the far side of the moon, plus a direct beam-back to the Earth at all times. The  Chinese did that with their Quèqiáo satellite, put in place. That was achieved on 14 June last year. That satellite in turn carried two microsatellites, the second part of the mission, called Lóngjiāng 1&2, which were to go into standard orbit around the moon. These were deployed on 21 May. Only Lóngjiāng-2 attained orbit, but it dutifully sent back pictures of the moon. It carries a camera developed by Saudi Arabia and it was tracked by amateur radio operators. The main purpose of these satellites is to test radio astronomy and interferometry techniques. The main satellite will also study the low-frequency radio regime, which is unexplored in astrophysical studies. This latter part was a joint venture between the Netherlands and China.

Chinese did that with their Quèqiáo satellite, put in place. That was achieved on 14 June last year. That satellite in turn carried two microsatellites, the second part of the mission, called Lóngjiāng 1&2, which were to go into standard orbit around the moon. These were deployed on 21 May. Only Lóngjiāng-2 attained orbit, but it dutifully sent back pictures of the moon. It carries a camera developed by Saudi Arabia and it was tracked by amateur radio operators. The main purpose of these satellites is to test radio astronomy and interferometry techniques. The main satellite will also study the low-frequency radio regime, which is unexplored in astrophysical studies. This latter part was a joint venture between the Netherlands and China.

The third part was the landing of Cháng’é-4. It landed in a large crater called Von Kármán. The lander carried a lunar rover, which they named ‘Yùtù-2’. The lander and the rover are to study the geophysics of the zone. They both carry several types of instruments and packages, some of which is classified. The lander is equipped with two cameras, a low frequency spectrometer, a neutron dosimeter developed with Germany, and a sealed biosphere to see whether or not plants and animals can grow together in synergy on the moon. This includes seeds of potatoes, tomatoes and a flowering plant along with silkworm eggs.

The lunar rover carries a panoramic camera, a lunar ground-penetrating radar, an imaging spectrometer, and a gadget called an ‘advanced small analyzer for neutrals’, provided by the Swedish. The latter will reveal how the solar wind interacts with the lunar surface and may give clues about the formation of water on the moon. The  landing site is symbolic and a tribute, as it is named after the man who was the PhD advisor to the man who founded the Chinese space program, Qian Xuesen. In addition, the total scope of the mission also aims to measure the temperature of the lunar surface over the duration of the mission, to study the solar corona and to explore the evolution and transport of coronal mass ejections between the sun and the Earth and to study cosmic rays. So, it is quite a package of instruments and investigations. The ultimate aim of the mission is preparatory for a manned landing on the moon in the 2030s, with aims of setting up a base.

landing site is symbolic and a tribute, as it is named after the man who was the PhD advisor to the man who founded the Chinese space program, Qian Xuesen. In addition, the total scope of the mission also aims to measure the temperature of the lunar surface over the duration of the mission, to study the solar corona and to explore the evolution and transport of coronal mass ejections between the sun and the Earth and to study cosmic rays. So, it is quite a package of instruments and investigations. The ultimate aim of the mission is preparatory for a manned landing on the moon in the 2030s, with aims of setting up a base.

Given the contributions of the Netherlands, Sweden, Germany and Saudi Arabia, this is an international effort, and not simply Chinese. There is a caveat here, though. What do we notice that is missing? The Americans. There is no American contribution to the mission. Alas, there are geopolitical rivalries and hints going on with Cháng’é -4, and they are worth noting. Apparently there is a little hiccup when it comes to the NASA and China collaborating on space missions – something to do with national security on the US side called the Wolf amendment, nicknamed after Frank Wolf of Virginia:

“None of the funds made available by this Act may be used for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) or the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to develop, design, plan, promulgate, implement, or execute a bilateral policy, program, order, or contract of any kind to participate, collaborate, or coordinate bilaterally in any way with China or any Chinese-owned company unless such activities are specifically authorized by a law enacted after the date of enactment of this Act.” (p. 96 of 878)

In other words, from one year ago. But it goes back years before that. Wolf had blocked any cooperation between NASA and China since 1996, when a Chinese rocket carrying a US satellite blew up at launch. The Chinese used the ensuing investigation to purloin secrets from the satellite, so Wolf’s concerns were not wholly unfounded. But the ban on cooperation has cost the US dearly. Space exploration is both highly competitive and very costly. The scientific community cheered when he retired in 2015 – of interest, three years to the day of the Cháng’é-4 landing. The ban will be lifted before too long, in all likelihood, especially after the success of this mission thus far.

From their side, the Chinese have had to approach other space agencies for cooperation, most notably European space agencies. We might also note here that there is no Russian component to this mission, given that Russia and China are increasingly joined at the hip these days. Well, it turns out that they just signed an agreement on space exploration in June of last year, which may include a joint mission of a moon base in coming years. And Putin wants to send a mission to the moon this year. If the US wants to keep up in the space race then it will have to cooperate increasingly with foreign powers. The other alternative is to divert funds from ‘defense’ spending toward space exploration and technological research, not to mention domestic infrastructure and social programs. Trump’s call for a ‘space force’ fits into this picture as well, and is likely based in the alarm at the pace in which the Chinese and Russians are advancing in their space programs, such as this Chinese mission.

The Americans had requested data for this mission from the Chinese, especially telemetry and satellite positioning, but were denied, both by the Chinese and by the Wolf amendment. It has to really hurt the scientists in the US, who are rightfully disgusted by the political dimension that has been foisted on them. Space exploration can be a great bridge between cultures and nations, and should be, and that takes us into the next section of this discussion: Chinese culture, Chinese astronomy and some more esoteric considerations, including the astrology of the mission and what it might mean. But first, what do all those Chinese names for their spacecraft mean? Well, that gives us some Clues for what is to come:

- Cháng’é: the Moon Goddess

- Quèqiáo: the ‘Magpie Bridge’

- Yùtù: the Jade Rabbit

- Lóngjiāng: the Dragon river

It’s quite poetic, really, unlike the more sterile or patriotic names we give to our missions in the West. And it is also a love story, in two parts. Go to Part II…

Featured pic from Chinese National Space Agency